InTrans / Sep 09, 2015

Animals abroad: The invasion of the species

Go! Magazine

posted on September 9, 2015

posted on September 9, 2015

In the first article, “Animals abroad: How did the livestock cross the road?” we talked about the safe transport of cattle, swine, and chickens. But what about animals that we don’t want to travel? These “invasive species” are not just nonnative to the ecosystem they’ve now decided to call home, but their presence can cause some really serious problems.

Invasive species often compete so successfully in their new ecosystems that they displace the native species while causing environmental and possibly human harm. And with a lack of natural enemies, the invasive species often thrive.

It is all that bad? But what can we do to stop them? Let’s break it down (one animal at a time).

Nonnatives

First up is the dark-colored lake trout, with its yellow or white underbelly and white spots spread out over their body, head, tail, and fins. These freshwater char live mainly in lakes in North America and Canada. In the continental US, lake trout are native to the Great Lakes and are a desirable fish in commercial fishing. In fact, in 1970, the stock of lake trout depleted in the Great Lakes to a low point due to pollution, overfishing, and presence of their natural predator—the lamprey (with its funnel-like sucking mouth). Restrictions had to be put in place until the stock was replenished.

They made the transition from native to nonnative when someone illegally brought and released the lake trout in Yellowstone National Park’s three lakes—Shoshone, Lewis, and Heart Lakes—in the mid-1980s. The lake trout was suddenly an invasive species! Why? They spawned and took over the lakes. From 1998 to 2012 the lake trout population went from 126,000 to 746,000, which is an increase of almost 500 percent in just 14 years!

So okay, the lake trout population went up. You’re probably thinking “Who cares?” Well, a native species to these lakes—the cutthroat trout—care very much. It turns out that the lake trout eat the same thing as the cutthroat trout (tiny crustaceans called “scuds”), which means less food and more competition between the fish. So to compensate, area fisherman are specifically only catching lake trout, hoping that the population will decrease to allow the native cutthroat to thrive once more. By ensuring that native species remain in an area, diversity of that area can be protected, which is important for overall ecosystem health.

Okay, so that was an example of environmental harm. What about a nonnative that could cause human harm?

Non-natives and human health

Next up is the potentially deadly West Nile virus (WNV). The West Nile virus strain is said to have originated in an area in Africa in the late 1930s, and then subsequently spread globally, with the first case in the Western Hemisphere identified in New York City in 1999. WNV is now considered to be an endemic pathogen. In 2012, the US experienced one of its worst epidemics—WNV killed 286 people.

So when you think of WNV, do you automatically think mosquitoes? If so, you’re not wrong; however, mosquitoes aren’t the only culprit. So how do the mosquitoes, who have a life span of 10 days, catch the virus and transmit it to humans? Well, mosquitoes actually transmit the virus from feeding on infected birds—who are the true carriers of the virus. When mosquitoes feed on infected birds, the virus gets into their salivary glands. During a “blood meal,” the virus can be injected in both humans and animals.

Some of the animals affected by WNV include horses, donkeys and mules. Other animals can be infected (like dogs and cats), but it is more uncommon, or, as some scientists speculate, when these types of animals are infected they don’t show apparent, outward symptoms.

What can be done to stop invasive species?

The obvious first choice is to prevent them from traveling in the first place. But if and when invasive species are introduced, a few actions can be taken.

First, early detection is vital. Once you let a species stay in an area long enough, they start to reproduce and become much more difficult to control. Currently, the National Wildlife Foundation (NWF) cites that federal and state agencies should be more equipped with technologies to catch invaders early.

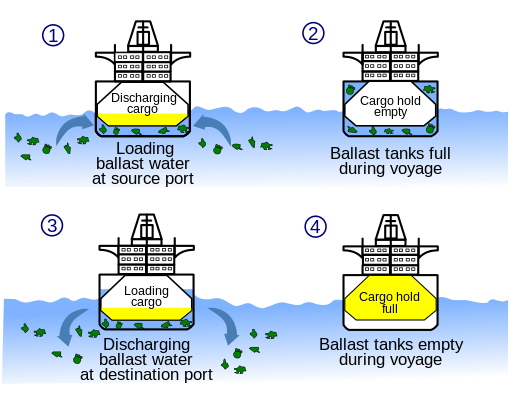

Additionally, one of the primary ways in which invasive species are introduced into US waters is through something called “ballast water” from ships. This is the water that is used to balance the ship during times of loading and unloading cargo.

This water increases the density of the ship, making it more stable on the water. Though it is important for maintaining ship buoyancy, the discharge of ballast water is said to have spread invasive species, including zebra mussels in the Great Lakes. The NWF recommends that the ballast water from ships—which can hold millions of gallons of water on larger ships—be treated before it is released.

Related links

http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=invasive.pathways

http://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/docs/council/isacdef.pdf

http://maritime.about.com/od/Ports/a/What-Is-Ballast-Water.htm

By Jackie Nester, Go! Staff Writer